Here is the transcript of my speech at the New Librarians’ Symposium (NLS9) in Adelaide 5-7 July, 2019. My slides have also been uploaded to SlideShare.

To begin, I’d like to acknowledge the Kaurna people as the traditional custodians of the land we meet today. I’d also like to pay my respects to Elders past, present and future, and acknowledge the living culture of all First Australians.

I’m really honoured to be speaking here at NLS9, but I’m also a little uncomfortable too. I’m uncomfortable because I’m a massive introvert, and am terrified at public speaking. I’m uncomfortable because I will be talking about a topic, that for whatever reason, generally makes a lot of people uncomfortable. And I’m uncomfortable that even in this day in age, we still need to have conversations about diversity, inclusion, equity and respect. Despite how uncomfortable I’m feeling, I’m here. I’m here because I care, and because I want to make a difference.

I care because I live with a disability that affects my vision, hearing, spine and joints. I’m hearing impaired and wear hearing aids every day. I’m also visually-impaired and loss most of my vision from a retinal detachment at the age of 13. This is what a lot of my life has looked like. And although my vision has improved over time, losing my sight taught me that to truly understand inclusion, you need to understand exclusion. You need to acknowledge inequality and privilege in our society, and you need to care enough to make a change.

Beyond my personal circumstances, I also care as a library professional because I believe diversity and inclusion is critical to the work we do. In libraries we talk about advocacy a lot, but I think we need to start looking at activism more. Beyond all the political connotations associated with these terms, an advocate is simply one who speaks on behalf of another person, group or cause. Whereas an activist is a person who acts with intentionality to bring about social change. To me, practicing radical activism means we facilitate community conversations, and work to diminish and ultimately eradicate systematic barriers. It means we ask difficult questions, have courageous conversations, practice compassion, and magnify voices and talents. It’s not necessarily about having the solutions but having the leadership to listen to ideas and bring communities to a table where everyone has a voice and is valued. I think we need to stop talking about people and start talking to people. Let’s collaborate, co-create and innovate with our communities. Let’s be the type of profession that acts with inclusivity through our day-to-day actions, not merely our advocacy work.

I think sometimes we get caught up thinking that since we’re all nice people, inclusion will just take care of itself, right? Libraries are open to everyone – we don’t discriminate, we don’t make money, we’re holders of diverse histories and diverse stories. However, inclusion doesn’t just happen because we have good intentions. We have to work for it. We need to need to have some uncomfortable conversations with ourselves as a profession and as individuals. How can we be inclusive if our structures oppress or exclude people? If diversity is not reflected in our spaces? If the way people can ‘belong’ is to change themselves rather than for our spaces, services and profession to change? These are questions that have been plaguing me for a while now. And although I don’t have all the answers, I wanted to share some tips that I have learnt from my personal and professional experiences on how we can make our libraries more inclusive.

Firstly, let’s start by being accessible. To quote Steve Krug, ‘the one argument for accessibility that doesn’t get made nearly often enough is how extraordinarily better it makes people’s lives. How many opportunities do we have to drastically improve people’s lives by doing our jobs a little better?’ As someone with a disability, access to me, is the floorboard of inclusion. I cannot tell you how many times I have been unable to see over a counter or reach something located on a shelf up high. I cannot tell you how many times I have been unable to read something simply because of the colour combination or font size, or because the content was inaccessible on a mobile device. Let’s lower our desks and our shelves. Let’s make sure our electronic content is accessible on screen readers and mobile devices. Let’s consider installing braille signage on doors, incorporating height-adjustable furniture into our spaces, and using Auslan interpreters at events. However, let’s also remember that it’s not just infrastructural changes that are important. I think sometimes we focus too much on the extraordinary goals that we forget small changes can often make the most difference. Small changes that each one of us on this room can do, as professionals and as part of the global community.

Small change 1: learn how to make your own content accessible

This includes:

- Structuring your documents logically (use headings)

- Adding image descriptions (Alt-image)

- Adding closed captions to videos

- And thinking about your use of colour contrast

I’ve embedded Vision Australia’s accessibility toolbar into my word documents. It’s free and is super easy to use. It runs accessibility reports and tells you how to fix the errors. With 80% of web content starting its life in Microsoft Word, it’s so important we get the accessibility of our word documents right (Vision Australia, 2019). Fixing accessibility errors only takes a few minutes of your time, but can make a profound difference to someone’s online experience.

On social media, you can also make your content more accessible by using camel hashtags. Capitalise each word in your hashtag as this makes it easier for people who are using text to speech software. For example, if you wanted to say ‘Nikki is doing an awesome presentation at NLS9’ you would do it like this – #NikkiIsDoingAnAweseomePresentationAtNLS9 – not like this #nikkiisdoinganaawseomepresentationatnls9

Small change 2: Expand your understanding of access

I also want you to expand your understanding of access. Accessibility is not only limited to ramps, or captions or braille. Accessibility goes beyond the realm of disability and can also include:

- Providing online participation options for events

- Breaking down barriers to access by supporting initiatives such as the open access movement and the Marrakesh Treaty to make it easier to reformat and repurpose content in response to requirements

- Providing gender neutral bathrooms

- Providing sensory safe spaces, with muted lights and colours

- And considering the needs of clients who are on the wrong side of the digital divide and finding ways to bridge that divide

Small change 3: Ask the person

I am sometimes asked for my recommendations on the types of font sizes, styles and colours we should be using for accessibility purposes, and the truth is, there is no concrete answer to these questions. People are so diverse that it’s impossible to accommodate everyone’s individual needs and circumstances. In fact, access and inclusion mean different things to different people (Government of Western Australia Department of Communities, 2019). Therefore, outcomes for access and inclusion are never going to be prescriptive. I can tell you that I like to read yellow font against a black screen often at a size 14 but I can’t speak on behalf of anyone else’s needs. So the best thing we can do to be truly accessible and inclusive is to leave our assumptions at the door and simply ask the person. If you have a client or colleague who has accessibility needs, just ask them what their preferences are and how you assist them. I am really so appreciative when people do this for me.

Small change 4: Apply Universal Design Principles

‘Universal Design is the design of products and environments to be usable to all people, to the greatest extent possible without the need for adaption or specialised design,’ (The Center for Universal Design, 2008). Sit-stand desks are a wonderful example of Universal Design as they are flexible enough to accommodate everyone’s needs, regardless of individual differences. Learn to apply Universal Design not only to your infrastructure, but also into all your programs, events and learning experiences.

This involves creating multiple means of representation, engagement and expression to accommodate people’s unique learning styles. Creating multiple means of representation means you present what you convey in different ways (e.g. audio-visual & written material). While creating multiple means of expression means providing flexible options for how people learn, express and share their knowledge (e.g. different communication channels). And last but not least, multiple means of engagement means providing flexible ways to generate motivation. This means creating experiences that are meaningful to people’s lives. When we create services or programs, we need to design them with various levels of interests in mind, as well as different levels of capabilities. Ultimately, Universal Design works on the premise that the more flexibility and diversity you provide, the more accommodating you become of people’s differences.

Small change 5: Deviate with diversity

When people walk into a library they should be able to see a part of themselves in their environment – that is the hallmark of an inclusive place. Creating an inclusive library means we put all kinds of faces on our marketing material. It means we have diverse artwork and diverse displays and not just for particular days of the year. It means we find out what is important to our communities and we target our services to those needs. This could mean translating content into different languages, shining a light on indigenous research methodologies, or making sure we’re aware of times of celebration in different cultures. It also means diversifying our collections so we are more representative of the glorious diversity within our communities.

When someone walks into a library and can’t find a book that represents them or their life, we have failed them. Likewise, if someone walks into a library and only see books that represent their life, we have also failed them. A survey on diversity in children’s books found that approximately 77% of characters were either white or an animal (Cooperative Children’s Book Center, 2019). Only 1% of characters were reflective of First Nations peoples, 7% were reflective of Asian Pacific heritage, and 10% were African (Cooperative Children’s Book Center, 2015). ‘When children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read, or when the images they see are distorted, negative, or laughable, they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in a society of which they are a part,’ (Sims Bishop,1990). This is why libraries play such an important role in promoting marginalised voices. Let’s undertake diversity audits to ensure our collections contain diverse resources, by diverse authors. This can be done by combing through the data in our online catalogue and by analysing the books themselves individually. Although it’s a lot of work, it highlights our biases – what voices we promote and what voices we marginalise. Collection management data helps us be more evidence-based and holds us accountable in ensuring our collections are diverse – which is so important – because without diversity our libraries are only telling one story, from one point of view, with one set of biases. Our world isn’t like that and our libraries shouldn’t be either.

Include programs and events that celebrate diversity in your workplace and library. I’m a big fan of the Human Library. For those of you who haven’t heard of the Human Library, it’s an initiative founded in Denmark that aims to break down prejudice and stereotypes through open conversations (The Human Library, 2019). The Human Library is a place where actual people are on loan – where you can ‘borrow’ someone and have enlightening conversations with them – whether they be a refugee, alcoholic, Muslim or sexual assault survivor. I know some Australian institutes have become local organisers of the Human Library, but I’d love to see more libraries do so. We need to create initiatives that celebrates diversity in a safe way – where we can remind our clients and ourselves that each one of us is the same by the simple fact that we are different – and there’s so much beauty in that.

Staff diversity is arguably just as important as diversifying our collections and services. Because how can we harness the true power of diversity if we don’t recruit and retain the very people we claim we want to include? Although diversity and equity is a core value of our profession (Australian Library and Information Association, 2018), we are lacking diversity in many demographics, with some literature stating that ‘we are paralysed by whiteness,’ (Galvan 2015; Vinopal, 2016; Larsen, 2017; Swanson et al 2015; Poole, 2019). In addition, research shows that even when we manage to recruit diverse talent, staff from underrepresented groups are leaving the profession at even higher rates than others (Vinopal, 2016). This is a warning sign for us to look critically at our workplace cultures and practices. For example:

- The existence of unpaid internships in LIS education is a significant barrier for low socio-economic students (Vinpoal, 2016)

- The term ‘cultural fit’ may be problematic in the hiring process and encourages recruiters to look for their ‘mini mes’

- The rigid distinction between ‘professional’ and ‘para-professional’ roles creates silos

- And bullying, harassment, burnout, power, exclusion and institutional oppression are all factors that may inhibit our ability to retain a diverse workforce

Having previously worked in HR as a Diversity and Inclusion Officer, I believe these issues come down to bias and a lack of self-awareness. Biases are the stories we make up about people before we know them. We all have unconscious bias – it’s a natural part of the human condition – but we need to learn to examine our biases.

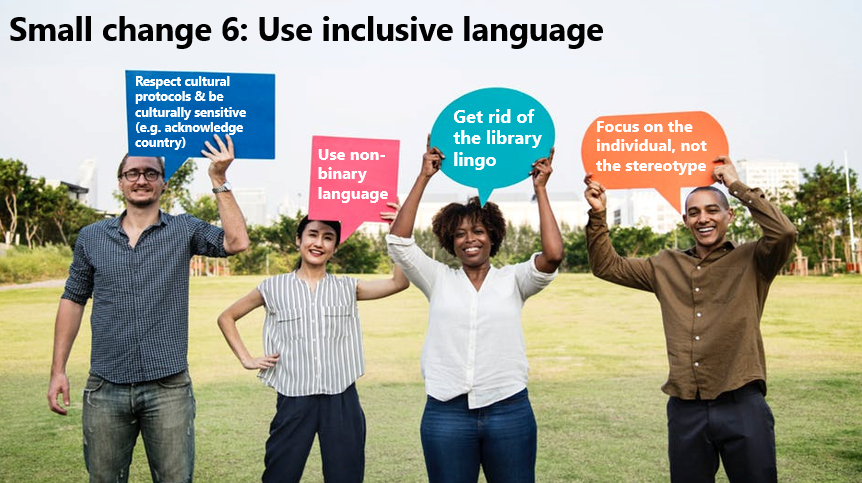

Small change 6: Use inclusive language

I think language is one of the most underrated but one of the most powerful enablers of inclusion. How we speak, write and visually represent others is so important. Firstly, let’s get rid of the library lingo. When we use language not commonly understood by others, we are automatically excluding them. Secondly, let’s use non-binary language. ‘They’ and ‘their,’ instead of ‘she,’ ‘he,’ ‘her,’ or ‘him. This is particularly important for the LGBTIQ+ community, as well as our work in achieving gender equality. For example, let’s use the word ‘firefighter’ instead of ‘fireman.’ Let’s also respect cultural protocols and be culturally sensitive, and lastly, let’s focus on the individual, not the stereotype. As someone with a disability, this is particularly important to me. Throughout my life I’ve heard phrases like ‘people who suffer from a disability,’ or ‘it’s so great to see you overcoming your disability.’ When you pity people, you disempower them. Yes, I’m disabled, and yes, I will always be disabled, and yet, I’m still happy with my life. I don’t ‘suffer’ from a disability, and I’ve never ‘overcome’ my disability. I just live with a disability. So I want to encourage you all to think about the language you use every day and ask yourself am I being kind and am I being empowering? Because what we say, and do, and write, and create truly matters.

Small change 7: Be a better bystander

Let’s also remember that non-inclusive language does not always include words, but also the absence of words. Every time we encounter racism, discrimination or harassment in our libraries, and we don’t say anything or don’t oppose the poor behaviour, we are in essence, endorsing it. Silence only ever encourages the oppressor, not the oppressed. We need to have the courage to be better bystanders, because unfortunately, the statistics here are pretty sobering:

- 1 in 5 Australians have experienced race-hate talk (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2014).

- 75% of youth who identify as LGBTIQ+ experience discrimination, with 6 in 10 experiencing verbal homophobic abuse (Cowell, 2019: Australian Human Rights Commission, 2014).

- 1 in 3 women have been sexually harassed (Ruiz & Ahn, 2015).

- And 56% of people with a disability face barriers to social inclusion (Australian Government Department of Social Services, 2012).

Libraries are supposed to be safe spaces for everyone, but when we don’t take action against inappropriate or exclusive behaviour, we are not providing our clients or colleagues with the psychological safety they deserve. In fact, if we look at inclusion through the lens of neuroscience, we find that inclusion is so important to everyone that it’s actually processed in the prefrontal cortex of our brains (Eisenberger, 2012). Research found that being excluded activates our pain systems, which means it’s a threat to our very wellbeing (Eisenberger, 2012). So when someone ignores our idea or perspective in our workplaces, or excludes us from a meeting we should have been at, the pain we feel is experienced in the same areas of the brain as actual physical pain (Eisenberger, 2012). The existence of this tangible social pain is evidence that connectivity, inclusion and belonging are so important. So, when we do encounter behaviour that jeopardises the notion of the library as a safe space, we need to be better bystanders. ‘That’s not okay,’ ‘you need to stop,’ or ‘we don’t do that around here,’ are all good bystander intervention starters. We also need to look critically at our current practices. Let’s revisit our policies and procedures, as well as assess our physical and online spaces to determine whether or not we truly provide a safe space for everyone (Wexelbaum 2016). Inclusion, in the simplest terms, is really about feelings – feelings of belonging, and paradoxically, feelings of uniqueness. It’s because of these feelings that creating an inclusive environment must start with the heart – the heart of libraries, the heart of the library profession, and the heart of each one of us as human beings.

It’s the people working in our libraries who make things happen, who create change, and bring values to life. I know a lot of you are probably thinking as new professionals that you don’t have the influence to create change in your library or workplace, but the truth is, you do, in each of your own unique ways. Just consider the effects of just ‘one small thing.’ One match. One mosquito bite. One minute. One vote. One seed. One words of kindness.

The power of small things leaves legacies, whether we realise it or not. Culture is what ordinary people do every day – it’s our smallest day-to-day interactions. Everyone has and makes culture, and I truly believe that the way we make people feel transcends the work we do – and we are all leaders when it comes to that.

But here’s the catch, creating an inclusive library is ongoing work, and not a check-the-box activity. In fact, it’s really really hard. I’ve screwed up, made mistakes and learnt a lot about myself and others through my advocacy and activism work for inclusion. But I keep striving for inclusivity one tiny step or change at a time, often quite imperfectly, but with a whole lot of passion.

I really hope you’ll join me, no matter how uncomfortable you feel.

References

Australian Government Department of Social Services (2012). SHUT OUT: The Experience of People with Disabilities and their Families in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/disability-and-carers/publications-articles/policy-research/shut-out-the-experience-of-people-with-disabilities-and-their-families-in-australia?HTML

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2014). Face the facts: cultural diversity. Retrieved from https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/education/face-facts-cultural-diversity

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2014). Face the facts: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People. Retrieved from https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/education/face-facts-lesbian-gay-bisexual-trans-and-intersex-people

Australian Library and Information Association. (2018). ALIA core values policy. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/about-alia/policies-standards-and-guidelines/alia-core-values-statement

Cooperative Children’s Book Center. (2019). Publishing Statistics on Children’s Books about People of Color and First/Native Nations and by People of Color and First/Native Nations Authors and Illustrators. Retrieved from https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp

Cowell, J. (2019). IDAHOBIT Day at the Library- what did we learn. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@janecowell8/idahobit-day-at-the-library-what-did-we-learn-c146a0301c1?source=rss-d5abbe75926c——2

Eisenberger, N. (2012). ‘The neural bases of social pain: Evidence for shared representations with physical pain,’ in Psychosom Med, 74(2), pp. 126-135.

Galvan, A. (2015). Soliciting Performance, Hiding Bias: Whiteness and Librarianship. Retrieved from http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/soliciting-performance-hiding-bias-whiteness-and-librarianship/

Government of Western Australia Department of Communities. (2019). Disability Access and Inclsuion Plans. Retrieved http://www.disability.wa.gov.au/business-and-government1/business-and-government/disability-access-and-inclusion-plans/

Larsen, S. (2017). Diversity in public libraries: strategies for achieving a more representative workforce. Retrieved from http://publiclibrariesonline.org/2017/12/diversity-in-public-libraries-strategies-for-achieving-a-more-representative-workforce/

Poole, N. (2019). Diversity within the Profession. Retrieved from https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/DiversitywithintheProfession

Ruiz, M & Ahn, L. (2015). Survey: 1 in 3 Women Has Been Sexually Harassed at Work. Retrieved from https://www.cosmopolitan.com/career/news/a36453/cosmopolitan-sexual-harassment-survey/

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). ‘Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Glass Doors.’ Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3).

Swanson, J., Damasco, I., Gonzalez-Smith, I., Hodges, D., Honma, T & Tanaka, A. (2015). Why diversity matters: a roundtable discussion on racial and ethnical diversity in librarians. Retrieved http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/why-diversity-matters-a-roundtable-discussion-on-racial-and-ethnic-diversity-in-librarianship/

The Center for Universal Design. (2008). About UD. Retrieved from https://projects.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_ud/about_ud.htm

The Human Library. (2019). The Human Library: a worldwide movement for social Change. Retrieved from http://humanlibrary.org/

Vinopal, J. (2016). The quest for diversity in library staffing: from awareness to action. Retrieved from http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/quest-for-diversity/

Vision Australia. (2019). How Microsoft Word can help you create accessible web content. Retrieved from https://www.visionaustralia.org/community/news/2019-03-29/how-microsoft-word-can-help-you-create-accessible-web-content

Wexelbaum, R. (2016). ‘The Library As a Safe Space.’ The Future of Library Space, 36, pp. 37-78.

5 thoughts on “Deviating with diversity, innovating with inclusion: a call for radical activism within libraries”